How do artists overcome the temptation to give up? The work of Max Beckmann offers a compelling story of moving forward amid turmoil.

Most of all, I remember the smell of the circus. The warm, humid air was sticky with the aroma of cotton candy, popcorn, pyrotechnics, diesel fuel, and elephant dung. My little kid legs were fused to the wooden bleachers like raw chicken to a hot pan. Tigers. Cannons. Cars with two steering wheels. The Flying Wallendas. Upside down motorcycles somersaulting around a flaming steel cage. At this moment, my pre-internet hometown of Grand Forks became Coney Island or Paris. I was transported.

Long since these magical nights, many circus operations have faced criticism for their treatment of animals. That makes sense. I can think of a lot of things they probably shouldn't have done. I remember the whips and snaps and cages. But mostly, I remember unadulterated fun.

A Refugee

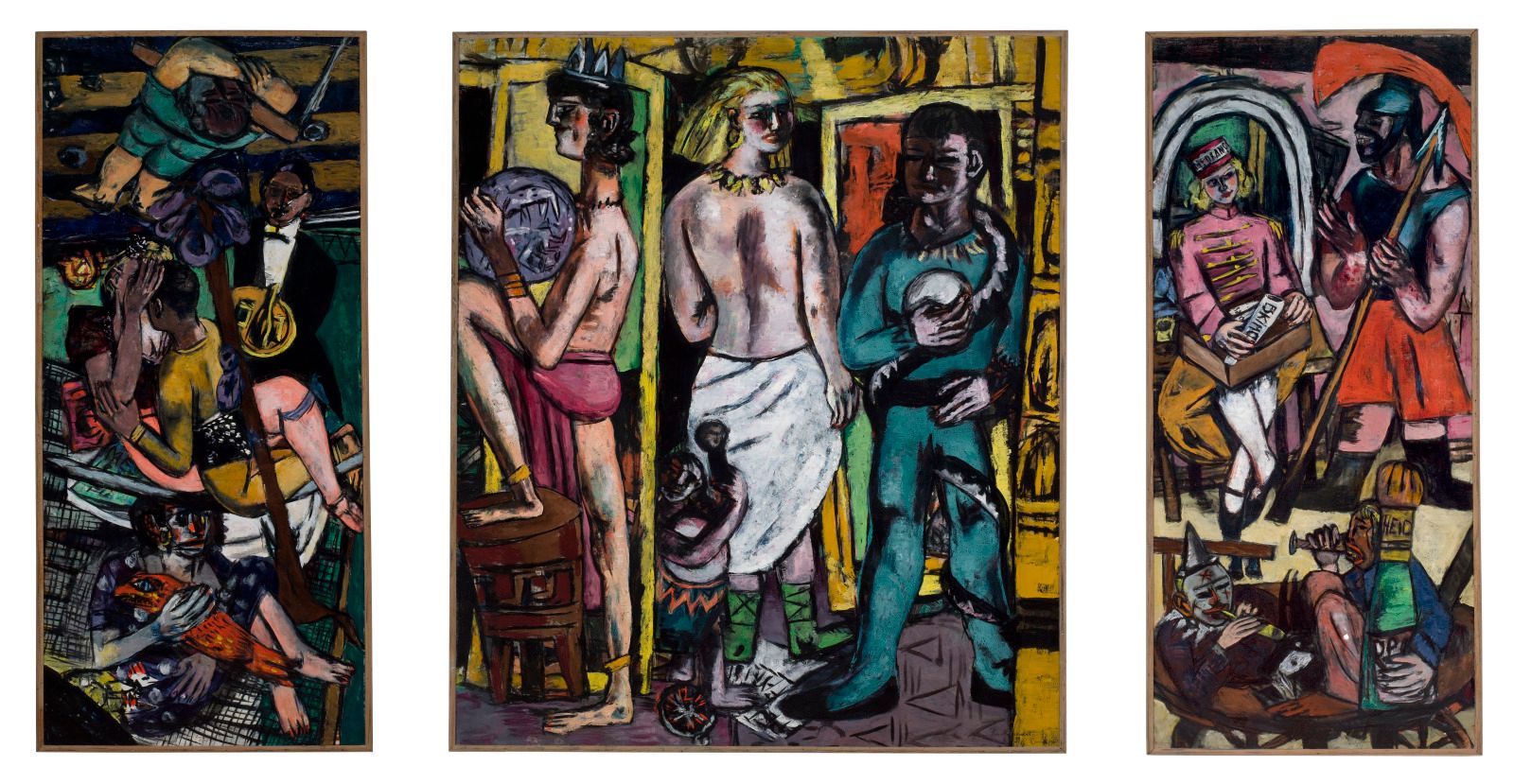

In Max Beckmann's 1937 painting, Acrobat on Trapeze, we see a muscular man squatting on a trapeze swing. Despite his strength, the acrobat seems aware of the precariousness of his perch. For the viewer, it is an impossibly intimate scene for someone we're used to cheering from a great distance. We see him. His proportions feel familiar—as though the image should appear in the camera roll of a mobile phone. Why is the man distracted from his act? Shouldn't his attention be elsewhere?

It is an impossibly intimate scene for someone we're used to cheering from a great distance.

Much of Beckmann's work reflects the tensions of being a creative person in a time of immense personal and social turmoil. During World War II, Beckmann, a German expressionist artist, was forced to flee Berlin to Amsterdam, where he lived from 1937 to 1947. Before leaving Germany, the Nazi government labeled him a "cultural Bolshevik" and removed him from his teaching position at the Städel Art School.

In Acrobat on Trapeze, the crowd feels distant and anonymous. A red Nazi banner looms large in the background. The Zubaz and slap bracelets of my childhood are painfully absent in this fascist circus, and Beckmann likely sees himself as the lonely acrobat—isolated from the nationalist fervor below.

What inspires me about Beckmann's work is his ability to press on despite his political dislocation. He fires up the popcorn machine and reappropriates the event as a vehicle for social commentary. Germany is the circus, and he is left dangling alone in Amsterdam. Despite being pushed out of his job and publicly rebuked as a "degenerate," he has the guts to take back the circus from the Nazis and make things sticky again. This isn't a happy scene, but it is an honest one. He is still here, but so is the Third Reich.

A Roadtrip

Beckmann teaches us about creative integrity. He is displaced from his home, his government, his career, and in a way, himself. His illustrations feel similarly displaced. They are odd in the same way that a circus act sets up a novel story between exotic characters and villains. Some are obscene. Many are mythical. Like clown makeup, he obscures the meaning of his portraiture through a level of absurdity and exaggeration. Everything is draped in coded social critique which liberates him to continue working without complete self-censorship. He refashions the brokenness around him and within as a vehicle for expression. He isn't a sad clown or a happy clown. He is the whole troupe.

This is what creative perseverance looks like—riding shotgun to your curiosity in a vehicle you have at your disposal to explore the places your questions drive you. You aren't on autopilot. You can try to navigate, but your senses won't always take direction. While it can feel frustrating at first, this tension will work for you if you learn to employ it. Beckmann's portfolio reveals these internal debates. Cynism, anger, lust, hope, humor, sadness, obsession, confusion, and loneliness. They all have a seat at the table, and they each have something to say.

This is what creative perseverance looks like—riding shotgun to your curiosity in a vehicle you have at your disposal to explore the places your questions drive you.

When you're on a road trip, it's easier to understand that a line segment represents a collection of points inside two endpoints. The key for Beckmann is that he doesn't ditch the car when he ends up places he least expects along the way. He plays connect-the-dots between history and the heart. He is the trainer and the tiger. He is the audience and the acrobat. This is a car with two steering wheels.

A Circus

There has never been a perfect time for a circus. It is always set against the backdrop of someone's pain. The state may use the circus as a tool for partisanship. Revolutionaries may use it as an act of subversion. And yet, the show must go on. There will always be artists who sing and dance and shoot themselves out of stuff. We need our hearts to race and our imaginations stretched by their vibrato. Yes, children require a healthy moral foundation and a good education. But they also need to see a man in leather chaps ride a flaming motorcycle across a tightrope while AC/DC screams over the PA.

There has never been a perfect time for a circus. It is always set against the backdrop of someone's pain.

The main event goes far beyond the big top in the internet age. We are pulled off the trapeze and into the Everywhere Circus of a thousand rings. All of this can lead us to work ourselves to death or throw up our hands and walk away. But if Picasso had tossed his brushes during his Blue Period, much of his most beloved work wouldn't exist today—not to mention his Rose Period (1901-1904), Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier) (1910), or Guernica (1937).

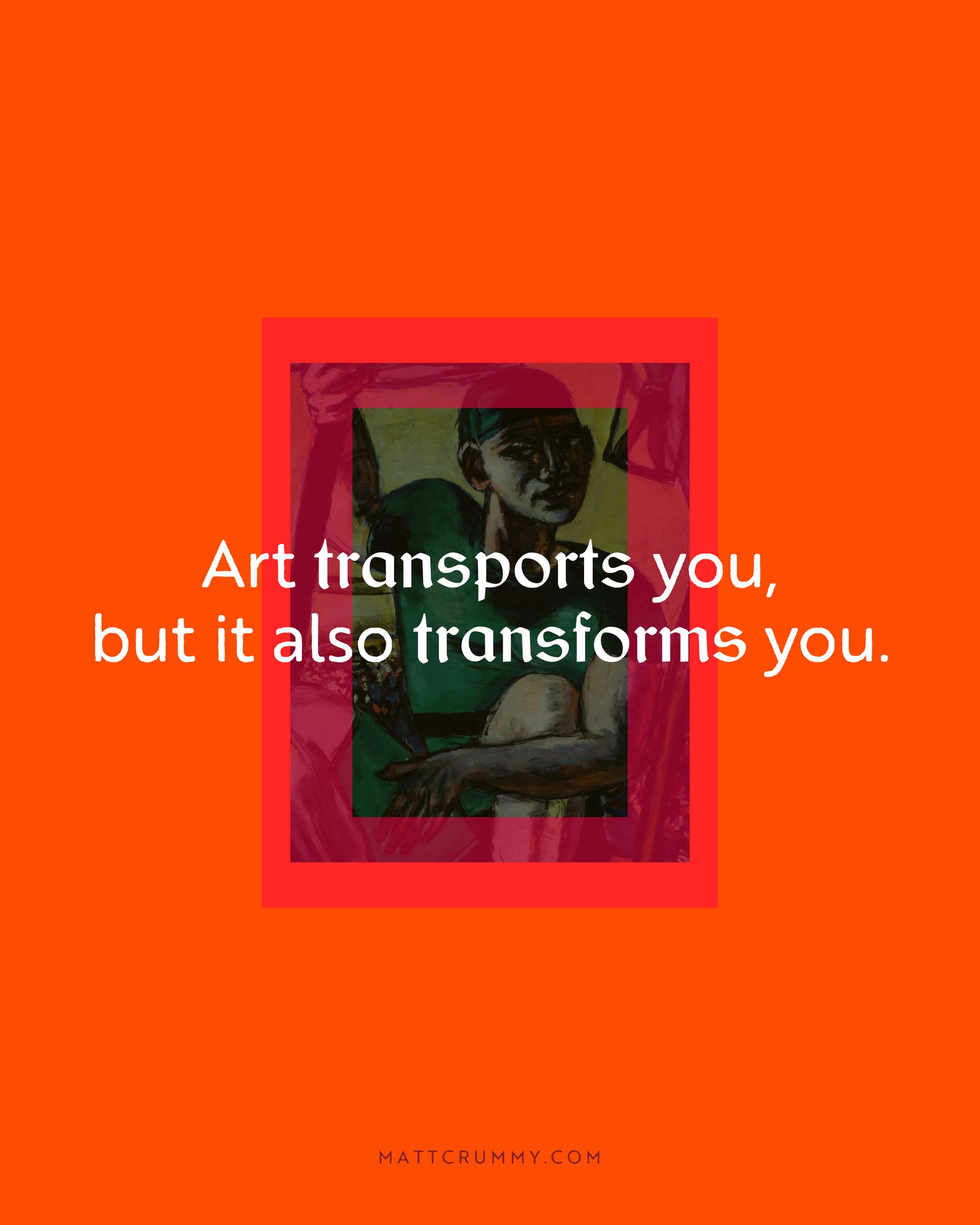

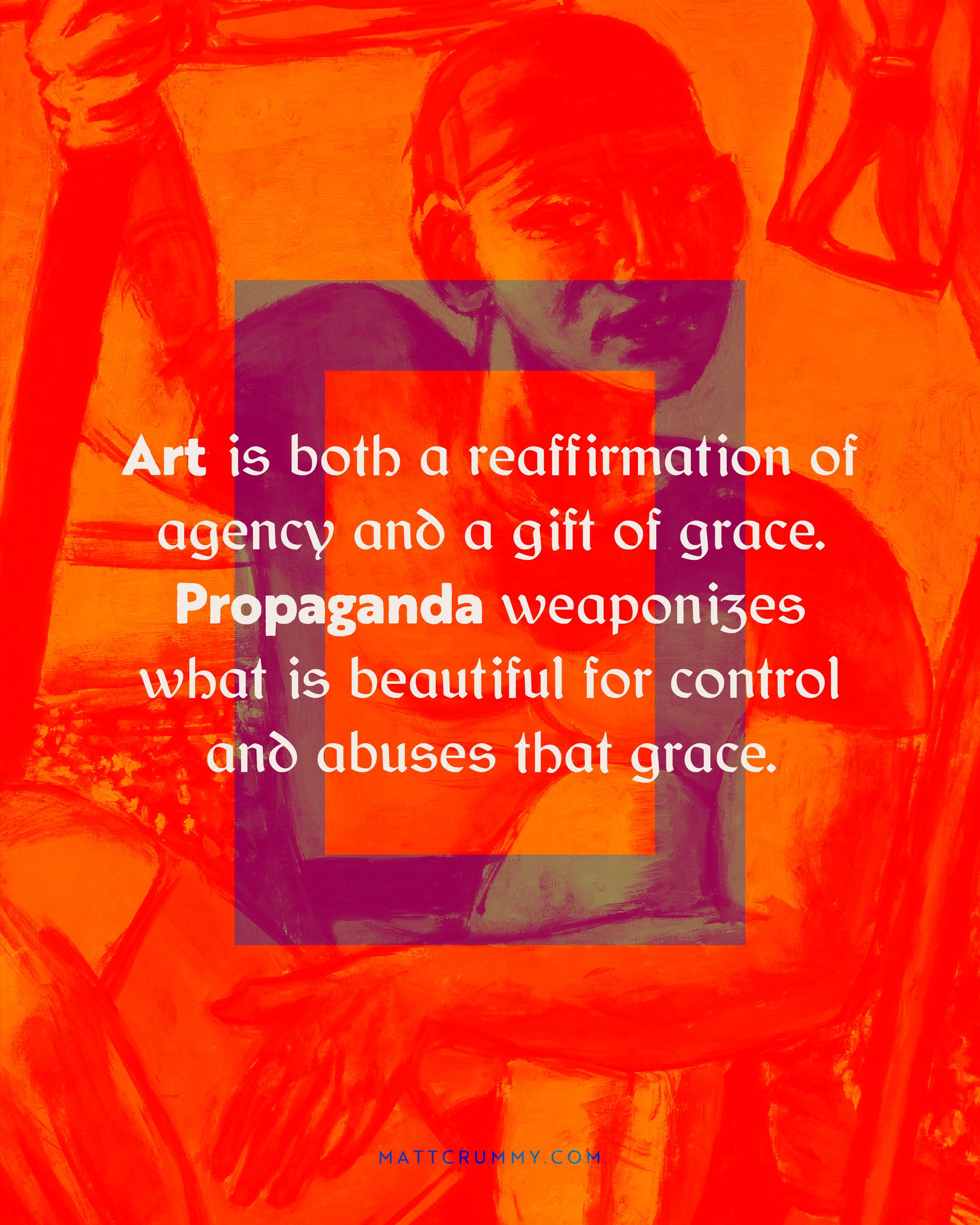

Art transports you, but it also transforms you. For a moment, an acrobat sailing through the air is all that matters. It peels back the curtain of the status quo and reminds us that our next steps are not inevitable. Art is both a reaffirmation of agency and a gift of grace. Propaganda weaponizes what is beautiful for control and abuses that grace. A reactive, defiant exuberance exists and declares, "I may be tired, but I am still here." If you are misunderstood in your efforts, it may take borrowed courage from someone like Beckmann to dust off your feet and move to the next town. But you must. We must. A kid with chicken legs is ready for Paris.

Share

Resources

https://www.moma.org/artists/429

Comments ()